The fundamentals

What is an ICD?

A small battery-powered device that can be implanted under the skin to monitor the heart for dangerous, potentially fatal heart rhythms. If it detects this it can try different techniques to try to stop the dangerous rhythm and ultimately it can even administer an electric shock to try to restore normal rhythm.

An ICD isn’t the same as a pacemaker, although both are implanted in a hospital and some types of ICD may look similar. However, a pacemaker is a device used to treat slow heart rhythms, an ICD treats fast, dangerous heart rhythms.

Do I need an ICD?

Ultimately this is always the patients choice. As healthcare professionals, we can share the latest evidence with you and what it suggests for people in your current situation. An ICD can help some people to live longer. It won’t change their symptoms or how often they have dangerous heart rhythms. But it can treat them if they do happen.

ICDs have greatest benefit in those people at highest risk of dangerous heart rhythms. The most powerful way to measure benefit in different patient populations is to conduct a randomised controlled trial- where patients with a specific heart condition are randomly allocated to either receive an ICD or not receive an ICD and then measure if there is significantly more benefit in either of the two groups. These were conducted around the World in the ’90’s and early ’00’s. Based on these studies, we know there are two groups of patients that live significantly longer if they have an ICD fitted. The clinical trials that showed the benefit are also described below.

Group1: Patients who have had a dangerous heart rhythm.

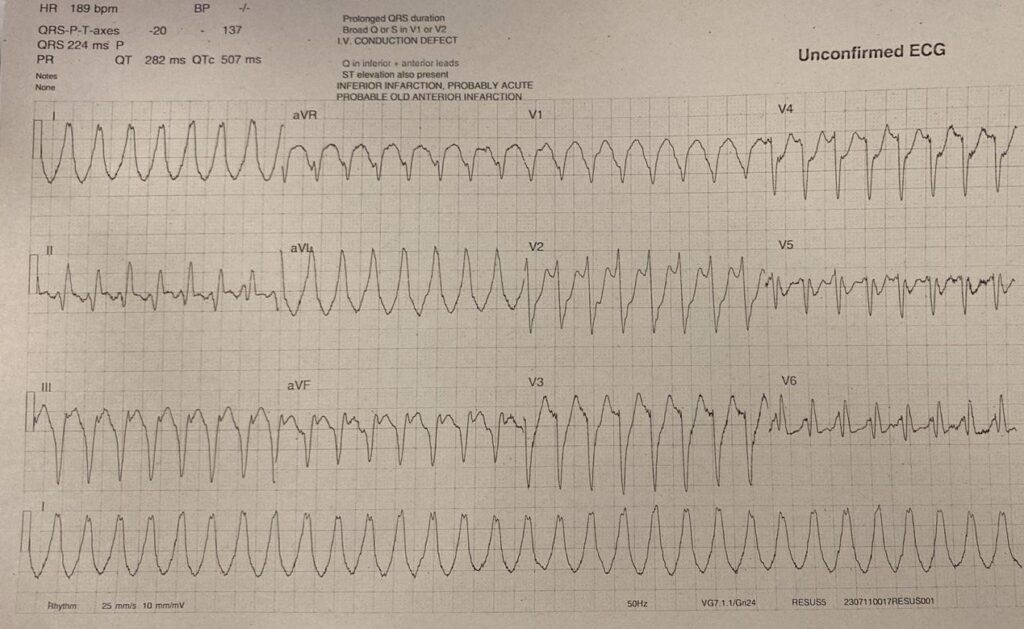

This is an ECG- an electrical tracing of the heart beat. It shows a dangerous, fast heart rhythm that can result in collapse or sudden death. If a patient receives the correct medical treatment in time, they can sometimes survive these events. But we know after one event, that person is at relatively high risk of having another one if a reversible cause is not identified and fixed. These patients who survive one event can benefit from ICD implantation.

The data supporting this:

The AVID trial: 1013 patients who had been resuscitated after one of these dangerous heart rhythms were randomised to receive either an ICD or drugs to suppress these rhythms. The trial found that patients treated with an implantable defibrillator had a better chance of survival compared to those treated with anti-arrhythmic drugs

The CASH and CIDS trials: These smaller trials looked at specific sub-types of dangerous heart rhythms. On their own, they showed potential benefit in arrhythmia-related survival and showed significant mortality benefit when combined in a summarised analysis of the CASH, CIDS and AVID trial patients who received ICDs.

Group 2: Patients who are at high risk of dangerous heart rhythms.

Patients with underlying heart conditions such as advanced heart failure or advanced cardiomyopathy may be at risk of dangerous heart rhythms. There are different ways to try and identify which of these patients are at highest risk and would benefit from an ICD. We know that in heart failure patients, weakening of their heart muscle can increase the risk of dangerous heart rhythms and this can be measured using an echocardiogram to take pictures of the heart as shown here.

The data supporting this:

The MADIT trial: focused on individuals who had previously had a heart attack and were left with a weakened heart muscle. In this study, all participants also had short, self-terminating runs of fast heart rhythm too. The study concluded that pre-emptive implantation of an ICD improved survival compared with similar patients that were randomised to receive conventional medical therapy only.

ScD-HEFT trial: enrolled 2521 patients who had congestive heart failure with weakened heart muscles and randomly divided them to receive either an ICD, a strong anti-arrhythmic drug called amiodarone, or heart failure tablets only. The results showed that amiodarone had no favourable effect on survival, whereas an ICD reduced overall mortality in these patients

Am I a ‘high risk’ patient?

This is a complex part of the decision-making process.

For patients who survive a dangerous heart rhythm (Group 1 patients), it will depend whether your doctor has identified a ‘clear reversible cause’ for your dangerous heart rhythm that can be fixed- for example a heart attack that is fixed with a stent or an overdose of drugs.

For patients who have not had a dangerous heart rhythm before but are considered to be at high risk, this depends on the underlying heart condition. For example, if you have a condition called Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy, doctors may estimate your risk using ‘Risk Calculators’ (also pioneered by doctors at Barts Hospital)

For patients with a weakened heart muscle:

- After an old heart attack,

- After a hospital admission for heart failure

- Incidentally detected on an echo scan,

- A genetic or structural heart condition such as Dilated Cardiomyopathy,

the risk is proportional to the weakness of the heart muscle, measured using an echocardiogram as shown here. Patients with severely weakened heart muscles (quantified using the left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) of less than 35% AFTER all medication options have been tried to restrengthen the heart are considered highest risk and this was also the group studied in the trials above.

How strong is the science behind ICD implantation?

A recommendation for ICD implantation in these groups of patients has been issued by both the European and American Cardiology Societies. The data has also been reviewed by NICE (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence) in the UK who have also issued a recommendation for ICD implantation in these patient groups.

How long would I live after ICD implantation?

An ICD is capable of treating only one potential cause of death- dangerous heart rhythms. Therefore, on an individual level, this is challenging to predict, because it relates to your individual risk of a dangerous heart rhythm which could be next week, next year or never. If and when that event occurs, an ICD is designed to try and terminate the rhythm and prevent death.

This being said, the studies described above provide some results about survival benefit on a group level. They report that the patients that had an ICD implanted after a first event (Group 1) lived on average 2-3 years longer and patients who had an ICD implanted due to their high risk (Group 2) had a 23-54% reduction in their risk of death compared to patients that did not receive the ICD over the 4-5 year time period of the study.

Questions in your Initial Consultation

How long does the ICD implantation take?

This will depend on several different factors:

- The type of pacemaker implanted

- The complexity of your anatomy

- How long it takes to find an optimal position for your leads.

But the procedure can last between one to three hours. Your length of stay in hospital will depend on whether you have other reasons for admission and on whether any complications occur. However, if the implantation is performed electively (i.e. you are coming into hospital specifically for the procedure) then you may go home on the same day.

Will the ICD implant hurt?

There are two components to this question:

Will the implantation procedure itself hurt?: If the procedure is performed under general anaesthetic then you will not feel anything. However, the vast majority of cases are performed under sedation (using injectable relaxants that induce sleepiness and reduce anxiety). You will also be given several forms of pain relief during the case. This will include local anaesthetic, injected into the area where the incision is made and the generator pocket formed as well as injectable pain relief through your veins that are short-acting but powerful enough to suppress the pain sensors in your body for a few hours. Some discomfort should be expected but most patients tolerate the procedure very well when performed under sedation.

Will the recovery after implantation hurt? Again, most patients do not find the post-implantation period painful but can experience some discomfort in the upper chest where the new generator sits. This is manageable with over-the-counter pain relief tablets such as paracetamol and we encourage patients to take this regularly for 1-2 days afterwards. The soreness can last for up to seven day, however if at any point the pain feels strong or as if it is getting worse we advise you to contact our Device Clinic team or your local A&E.

Would a shock from the ICD hurt?

An ICD shock can feel like a sudden kick to the chest. However, the intensity of the shock can vary from person to person. The device is designed to try painless manoeuvres first and only deliver a shock if the heart rhythm is potentially fatal.

What if I declined an ICD implantation?

ICDs are designed to treat dangerous heart rhythms. There are medications that can be trialled to reduce the likelihood of dangerous heart rhythms from starting but these can be used in combination with ICDs, not in place of them as they do different things.

The alternative to having an ICD is not having an ICD. Some patients may choose this if they would not wish to have these heart rhythms treated and would prefer to pass away naturally if they were fatal.

There are also different versions of ICD devices and more information about them is provided below.

What are the different types of ICD?

The most commonly implanted type of ICD is a ‘trans-venous’ system i.e. one that looks like a pacemaker and connects the device to the heart using leads. This was first implanted in 1980 in the USA and is the type used in all the trials reported above- so we have a lot of data on it.

Many patients who need an ICD have underlying heart issues that may benefit from the additional pacemaker functionality that this type of ICD can offer. However, it is important to review the newer types of ICD device that may be better suited to some groups of patients. Note:

Size

- S-ICD

- S-ICD vs transvenous ICD

- EV-ICD

What are the possible risks of ICD implantation procedure?

All medical procedures carry some risks, which must always be weighed carefully against the significant benefits. ICD implantation is generally safe and straightforward; in fact, the vast majority of patients experience no complications and are able to return home the same day. Below, we’ve clearly listed potential complications, grouped by when they might occur—immediately, shortly after, or long-term.

Immediate Risks (during or right after procedure):

- Failure to complete procedure (1 in 50)

Technical difficulties may prevent successful implantation; alternative plans discussed if needed. - Allergic reaction to contrast (Fewer than 1 in 100)

Rare immune reaction to injected dye, causing itching, swelling, or breathing difficulty. - Pneumothorax (collapsed lung) (Fewer than 1 in 100)

Air trapped around the lung, causing chest pain and shortness of breath; may require drainage. - Arrhythmia (abnormal heart rhythm) (Fewer than 1 in 100)

Temporary irregular heartbeat during procedure, may require immediate treatment. - Cardiac tamponade (fluid around heart) (1 in 200)

Fluid buildup compressing heart, potentially life-threatening, requiring urgent drainage. - Damage to surrounding structures (1 in 200)

Possible injury to heart or valves during implantation. - Haemothorax (blood around lung) (1 in 500)

Blood accumulation near lung, potentially requiring drainage.

Early Risks (days after procedure):

- Discomfort (More than 1 in 20)

Mild pain or stiffness for days/weeks; managed with pain relief. - Inappropriate shocks (Fewer than 1 in 20)

Device may deliver unnecessary electrical shocks; uncomfortable and may need adjustment. - Haematoma (blood collection) (Fewer than 1 in 20)

Localized blood collection, potentially requiring drainage if large. - Lead displacement (Fewer than 1 in 20)

Leads may move from original position; significant displacement may require repositioning. - Infection requiring device removal (Fewer than 1 in 100)

Serious device infection typically requiring complete removal. - Wound infection (1 in 1,000)

Skin or deeper tissue infection at incision site; antibiotics or further procedures may be necessary. - Death (1 in 1,000)

Very rare but a complication leading to fatality during the procedure or recovery period is possible.

Late Risks (months or years later):

- Generator and lead erosion (Fewer than 1 in 100)

Device components may wear through tissue or skin, potentially requiring replacement. - Device failure (Fewer than 1 in 100)

Rare malfunction causing failure to detect or treat arrhythmia, potentially dangerous.

The ICD implantation procedure

Scheduling your appointment

Once you and your doctor have decided that an ICD is the right treatment for you, you will be added to our waiting list for the procedure. The typical waiting time is between 4 and 12 weeks, but this can vary depending on how urgently your procedure is needed.

At St Bartholomew’s, our scheduling team carefully manage the operating lists and allocate appointments. Our schedulers will contact you with your procedure date, and this is usually with several weeks’ notice. You will also be given a date for a pre-assessment appointment before your procedure, where a nurse specialist will discuss important details with you. We run several implant lists each day and do our best to use any available slots that arise from cancellations too. You may therefore be contacted about an appointment at short notice. To help reduce waiting times, we also hold implant procedures on weekends.

Please be aware that if your procedure requires a general anaesthetic, there may be a longer wait as this also depends on the availability of a cardiac anaesthetist and a suitable recovery bed to monitor you after your procedure. Similarly, if you are scheduled for a specific type of ICD like an S-ICD or EV-ICD, the waiting time might be a bit longer as these require a cardiac electrophysiologist with specialist training and accreditation.

An important exception to this is if you are a Group 1 patient, meaning you have been hospitalised following resuscitation after a dangerous heart rhythm event. In these high-risk situations, it is likely that you will remain in the hospital until your ICD can be fitted, rather than being discharged home beforehand.

Pre-assessment

This is an important step to ensure your procedure goes as smoothly as possible. You’ll meet with an experienced nurse specialist a few weeks before your actual procedure date. This will either over the phone or in person at St Bartholomew’s Hospital in the East Wing building.

Our Pre-assessment Lead, Sarah Way explains what you can typically expect:

Your pre-assessment apppointment can include:

• Health Checks: The nurse will perform routine checks, including taking your blood pressure and swabs for any skin infections.

• Blood Tests: You’ll likely have some blood tests done if you are attending in person, or we may contact your GP for recent results. These help us to check things like your kidney function and to look for any signs of underlying infection.

• Addressing Potential Issues: If any issues are picked up during these checks or blood tests, the nurse will report these back to your doctor. This allows the medical team to consider how it might affect your procedure and to take any necessary steps beforehand. For example, if a minor infection is found, you might be prescribed antibiotics before your implant. Similarly, if your kidney function is a bit reduced, your doctor might need to adjust some of your medications.

• Medication and Meal Instructions: The nurse will give you clear instructions about what to do the night before your procedure. This will include guidance on which medications you might need to stop taking and the specific time for your last meal before coming to the hospital. You will also be told what time to arrive on the day.

• Procedure Details: The pre-assessment team will also go through the ICD implantation procedure in detail with you. They will explain what to expect on the day of your procedure and will also give you an idea of when you can expect to be discharged from the hospital afterwards.

• Your Questions: This is also an opportunity for you to ask any questions you may have. Whether it’s something your doctor hasn’t covered or a thought that has just popped into your head, please don’t hesitate to ask.

The night before

The night before – avoid alcohol, get good sleep, meds, pack an overnight bag

On the day

On the day

[Video]

After ICD implantation

Do’s an Don’t for the first month

- The area where the ICD is placed may be swollen and tender for a few days or weeks.

- For four weeks, do not make any sudden movements that raise your left arm above your shoulder. This is to reduce the likelihood of the device wires moving before the area is healed.

- Avoid heavy lifting and strenuous exercise.

- Keep your incision site dry.

- Avoid contact sports and water activities.

- Take your medications as prescribed.

- Attend all follow-up appointments.

- The stitches in the wound dissolve over time, so you do not need to have them removed. Your doctor may use a type of clear glue to cover the wound. Again, this won’t need to be removed by you.

When to seek help

- This will be explained to you before you leave hospital and you will be given the ICD clinic’s direct contact details:

- If you experience chest pain, shortness of breath, or rapid heart rate.

- If your ICD delivers a shock.

- If you notice any signs of infection at your incision site.

- If your ICD device is malfunctioning.

Follow-up

Your first follow-up appointment will be 4-6 weeks after your ICD implantation. You should have been given a date and time before you left the hospital. If you did not, you can contact the Device Clinic to check when this has been scheduled for or to re-arrange your appointment.

Your appointment will be conducted face-to-face so we can review how the wound has healed, and review the settings of the Device to see if anything needs optimisation. This is also a good opportunity to ask your Device Physiologist (an accredited and trained expert in Cardiac Devices) any questions that have arisen since implant.

Chris Monkouse, Chief Cardiac Physiologist summarises what to expect from your appointment.

Living with an ICD

An indirect objective of ICD implantation is to help patients return to a normal life.

Alex Wise, Arrhythmia Nurse Specialist at Barts Heart Centre covers some of the practical aspects to help achieve that recovery.

Long-term considerations

MRI scans

You may need to have your ICD temporarily deactivated before an MRI scan.

Airport security

Inform security personnel about your ICD before going through metal detectors. You will be given an official card to show them too.

Mobile phone use

Keep your mobile phone away from your ICD to avoid interference.

Power generators

Stand at least 2 feet from welding equipment, high-voltage transformers or motor-generator systems. If you work around such equipment please tell your doctor beforehand.

Can I exercise after ICD implantation?

Does having an ICD count as a disability?

Can I drink alcohol if I have had an ICD implanted?

Can I drive after ICD implantation?

You must inform the Driving and Vehicle Licensing Agency (DVLA) and your insurance company that you have been fitted with an ICD because abnormal heart rhythms can affect your ability to drive safely.

You must not drive for between 1 to 6 months following your ICD implant. The amount of time depends on the reason your doctor has recommended the ICD. Your implantable cardioverter defibrillator ( ICD)

You must also stop driving for at least 6 months and inform the DVLA if you have symptomatic anti tachycardia pacing (ATP) and / or shocks from your ICD at any time.

Please ask your cardiologist or healthcare staff at the ICD clinic for further advice.

For more information, please see the DVLA website: www.gov.uk/defibrillators-and-driving

Can I have sex after ICD implantation?

For most patients, having sex is not a medical risk. The natural heart rate increase that happens during sex is the same as the heart rate increase when you exercise. If you receive a shock during sex, your partner may feel a tingling sensation. The shock is not harmful to your partner.

How will I know when the ICD battery is low?

Generator change

Your ICD’s battery will eventually need to be replaced. This will usually be after 8-10 years.

The procedure is similar to the initial implantation, although much simpler.

Your cardiologist will schedule this procedure.

ICD de-activation

If you have an ICD and become terminally ill, your ICD still delivers shocks if it isn’t turned off. A healthcare professional can perform a simple procedure to turn off the ICD with your agreement. Turning off an ICD does not mean that your heart will stop. It means that the device will not treat or shock you if you have a fast, dangerous heart rhythm. Turning off the device can prevent unwanted shocks at the end of life.

Talk to your healthcare team about your wishes. Also talk to family members or the person chosen to make medical decisions for you in an end-of-life care situation.